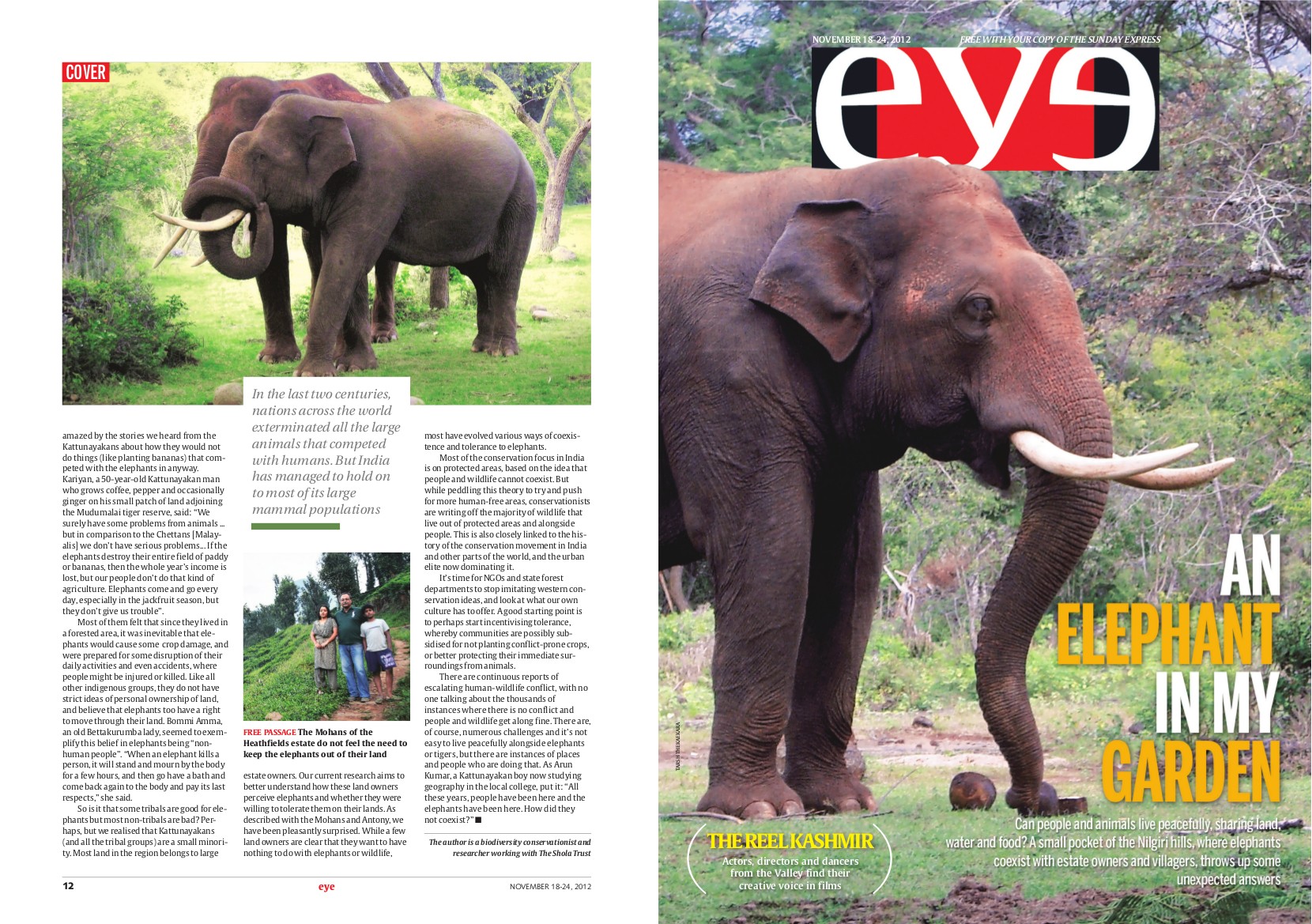

Can people and animals live peacefully, sharing land, water and food? In Gudalur forest division in the Nilgiri hills, where elephants coexist with estate owners and villagers, we found unexpected answers.

“I keep our gate locked during the day to keep unwanted people out. But I leave it wide open at night, to allow the elephants to move in and out, without having to knock the gate down.”– Harikrishnan Mohan, owner of Heathfields estate in Gudalur

Sangeetha and Harikrishnan Mohan and their children live on a 60-acre estate off the road between Ooty and Gudalur, in the Nilgiris. Their land covers one side of a hill, with their house in the middle and a mountain stream gushing by. Most of it is planted with tea along with some coffee, and about 15 acres are “undeveloped” private forests. They share the land with a range of wild animals — sambar deer, leopards, wild dogs (dhole), the occasional gaur and, most importantly, elephants.

They are full of stories about the elephants and appear to know them individually. A herd of 14 often walks through the estate, along with two males — one 25-year-old, who is clearly identifiable by his single tusk, and an older makhna (a tusk-less elephant), who has a damaged right ear. “The herd comes right up to the verandah. Last week, there were seven of them, they ate up all the flowers, but didn’t do any other damage,” says Sangeetha. The two males come to the house more out of curiosity, almost to explore. The estate owners make sure they don’t leave any salt or grain around to attract the elephants. Once the makhna, in a playful mood, started pushing their Scorpio and nearly sent it hurtling down the hill. Despite that, the Mohans don’t feel the need to stop the elephants from entering their land.

In summers, when the streams dry up, the elephants break the pipes inside the estate to get at the water. Now the Mohans have devised an intricate system of water sharing. They built an open tank on their land, halfway down the hill. The pipeline is broken at this point, with the water flowing in and out of the tank, so that both humans and elephants have access to water.

The Mohans are not an exception in the Gudalur forest division, sitting between the Mudumalai tiger reserve and the Mukurthi national park. It is what conservationists call a “matrix habitat” — a mixture of forests, large estates and small agricultural holdings, inhabited by people and a few hundred elephants.

When CM Antony, another estate owner, bought the land 50-odd years ago, they noticed an elephant path running through it. They decided not to plant tea in this area, and left the natural vegetation undisturbed. Elephants use this unmodified strip through their land, without causing much damage elsewhere. Except of course, in the late summer and early monsoons, when the jackfruits ripen and the elephants have a free run of the land. “We do have considerable damage from elephants on the whole, but actually we are quite proud of it. Whenever relatives and friends come over, we walk them through our estate and show them all the signs of where the elephants have been and what they have done,” says Antony.

Stories of such intricate systems of coexistence abound in the region — even though elephants and animals regularly break houses and damage small crops. They do not, however, eat the major crops — tea and coffee. Human injury or death due to accidental encounters with elephants is the most serious “conflict” element. But while estate owners like B Ravindran tell affectionate stories about “their elephant”, they also have a respectful “fear” of wild animals.

I work as a wildlife researcher and conservationist in the Nilgiris. My main interest is to better understand how wild animals, elephants in particular, can be conserved outside of areas like wildlife sanctuaries and national parks. The conventional wisdom in the field of conservation science is that people and wildlife cannot coexist, and the efforts so far have been to create small human-free “protected areas” (PAs) for wildlife, where most of the research efforts have been focussed. We have done a reasonably good job of protecting these pockets, and have also come a long way in understanding natural systems and the ecology of our forests and wildlife better.

But little effort has gone into understanding what happens beyond these spaces, where people and wildlife regularly interact. Since our protected areas cover less than 5 per cent of our land surface and are too small to host a viable population of any of our large mammals, conservation outside these areas, in the other 15-20 per cent of non-protected forests and agricultural areas, is now critical to safeguarding the future of these species. Having grown up in this region with lots of exposure to wild animals alongside people, I was a little sceptical of the “all-people-are-bad-for-wildlife” basis of most conservation science.

As most nations across the world “modernised” and developed sophisticated technology in the last two centuries, they exterminated the other large animals that competed with them for space and resources. Wolves, bears, mountain lions, moose and wild horses have been wiped out from most of their ranges across Europe and North America. Even Japan exterminated its wolves around 1900.

In this global scene, India poses something of a paradox. We have arguably had the technology to wipe out our large mammals for quite a while, and in spite of having an extremely high population density of about 400 people per sq km, we have still managed to hold on to most of our large mammal populations. Elephants and tigers have, of course, reduced significantly in numbers, but they are a lot more challenging to live with than moose and wolves. Wildlife biologist Dr Vidya Athreya has studied leopards that live almost exclusively in agricultural areas, with no surrounding forests, and almost no conflict with the local people either. She firmly believes that “there are a lot more animals out there living alongside people. It’s just that there are no scientists looking”.

What aspect of Indian culture makes people more tolerant to wildlife and able to share space? Perhaps it is the sacredness of various life forms in Hinduism, which reveres an elephant as a god, or the fact that Indians on average eat less meat than most people in the world, but no one fully understands our “cultural tolerance” to wildlife.

Another interesting element of “human-wildlife coexistence” are the indigenous communities who have lived relatively peacefully alongside wildlife for centuries. Traditional hunter-gatherers see the forests and all the animals in it as “non-human persons”, and believe that as long as they treat the forests well, they will be looked after unconditionally. There is no need to hoard resources or save things for later or strive for a “better life” like other modern societies do, since the forest is always there to take care of their needs. A few decades ago, well-known anthropologist Nurit Bird-David from Israel came to the Nilgiris in search of the “near pure hunter-gatherer”, and spent a year with the Kattunayakan tribals living in Glenrock village, close to Gudalur. She has since written numerous papers about them, and argued that their world view did not change even when they moved out of the forests and become a part of the mainstream as wage labourers. Instead of spending the day walking around the forests gathering food, they work for a day, collect the money and buy food from the local shop.

Our research attempted to understand the differences between communities, all living in the same region (within 500 m of the boundary of the Mudumalai tiger reserve) and interacting with the same wildlife. We interviewed 250 people from three tribal communities — the Paniyas, Bettakurumbas and Kattunayakans — and two non-tribal — the Chettys and Malayalis. We asked them about the extent of conflict between people and elephants, and tried to quantify “tolerance”. There were, of course, tremendous differences between the different ethnic groups, with the Kattunayakans being the most tolerant, and the most recent immigrants, the Malayalis, being the least tolerant. We were amazed by the stories we heard from the Kattunayakans about how they would not do things (like planting bananas) that competed with the elephants in anyway. Kariyan, a 50-year-old Kattunayakan man who grows coffee, pepper and occasionally ginger on his small patch of land adjoining the Mudumalai tiger reserve, said: “We surely have some problems from animals … but in comparison to the Chettans [Malayalis] we don’t have serious problems… If the elephants destroy their entire field of paddy or bananas, then the whole year’s income is lost, but our people don’t do that kind of agriculture. Elephants come and go every day, especially in the jackfruit season, but they don’t give us trouble”.

Most of them felt that since they lived in a forested area, it was inevitable that elephants would cause some crop damage, and were prepared for some disruption of their daily activities and even accidents, where people might be injured or killed. Like all other indigenous groups, they do not have strict ideas of personal ownership of land, and believe that elephants too have a right to move through their land. Bommi Amma, an old Bettakurumba lady, seemed to exemplify this belief in elephants being “non-human people”. “When an elephant kills a person, it will stand and mourn by the body for a few hours, and then go have a bath and come back again to the body and pay its last respects,” she said.

So is it that some tribals are good for elephants but most non-tribals are bad? Perhaps, but we realised that Kattunayakans (and all the tribal groups) are a small minority. Most land in the region belongs to large estate owners. Our current research aims to better understand how these land owners perceive elephants and whether they were willing to tolerate them on their lands. As described with the Mohans and Antony, we have been pleasantly surprised. While a few land owners are clear that they want to have nothing to do with elephants or wildlife, most have evolved various ways of coexistence and tolerance to elephants.

Most of the conservation focus in India is on protected areas, based on the idea that people and wildlife cannot coexist. But while peddling this theory to try and push for more human-free areas, conservationists are writing off the majority of wildlife that live out of protected areas and alongside people. This is also closely linked to the history of the conservation movement in India and other parts of the world, and the urban elite now dominating it.

It’s time for NGOs and state forest departments to stop imitating western conservation ideas, and look at what our own culture has to offer. A good starting point is to perhaps start incentivising tolerance, whereby communities are possibly subsidised for not planting conflict-prone crops, or better protecting their immediate surroundings from animals.

There are continuous reports of escalating human-wildlife conflict, with no one talking about the thousands of instances where there is no conflict and people and wildlife get along fine. There are, of course, numerous challenges and it’s not easy to live peacefully alongside elephants or tigers, but there are instances of places and people who are doing that. As Arun Kumar, a Kattunayakan boy now studying geography in the local college, put it: “All these years, people have been here and the elephants have been here. How did they not coexist?”

By Tarsh Thekaekara