‘Terra Preta’ is the most fertile soil in the world, found in pockets in the Amazon Basin. It was created by the indigenous people of the region about 5000 years ago, and was able to support much higher population densities than previously imagined. The key ingredient was charcoal (produced through by burning any available biomass in low oxygen conditions, a process called ‘pyrolysis’). The charcoal was mixed with a range of organic matter (manure, compost, animal waste and bones etc.) to make biochar, and was buried in the soil.

In recent years there has been a renewed interest in biochar because of the role it could play in climate change. In addition to the soil fertility, burying charcoal is also a way of sequestering carbon. As plants grow they absorb carbon (in carbon-dioxide), and when they die and decompose this carbon is released back into the atmosphere. But if the plants are converted into charcoal and buried this carbon is then locked up in the soil.

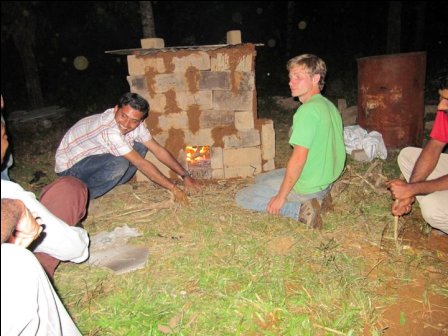

We are attempting to create terra preta in the Gudalur region, experimenting with different ways of producing charcoal, and trying to measure the improved agricultural productivity with biochar mixed into the soil.

Our work is largely at two levels:

1) On a household level – We are experimenting with families using biochar stoves. These are not only more fuel efficient and produce less smoke than the traditional stoves, but also produce charcoal as a by product, which can be mixed with manure/compost to make biochar and enrich soils on people’s agricultural lands.

2) At a more regional level – We are trying to use Lantana camara (a hugely problematic invasive plant that is taking over vast tracts of forests) as raw material for our charcoal producing kiln. Every year, tonnes of lantana are pulled out by the forest department and left to decompose or burnt inside the Mudumalai Tiger Reserve. This could instead be a huge source of biochar – that enriches the soils and sequesters carbon.